Baraboo, Wisconsin is a relatively sleepy town, about 45 miles north of Madison, the state’s capitol. Statewide, it’s known as the home of the International Crane Foundation and original home to the Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus.

Yet internationally, it’s now known as the place where almost every male in the current senior class gave a Hitler salute in a photograph taken earlier this year.

In a Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel article, a longtime Baraboo city administrator was quoted as saying, ““This isn’t Baraboo. This isn’t who we are.”

But that’s not the truth. Not the whole truth, at least. The high school has dealt with other incidents of bias in the recent past, and some students are going on record to say that they have felt intimidated or threatened at the school.

If we’re going to talk about the whole truth, we have to talk about not just Baraboo, and the mirror that is being held up to it. The fact that every state has a town like this. Not just one town, either.

For America to heal its hate, it’s going to have to not sweep it under the rug. It is not a coincidence that hate is bubbling to the surface. People who identify as minorities are not at all surprised. They’ve seen it coming.

No one need open the figurative Rolodex to flip through the huge uptick in hate. Incidents are rolling in and washing over us every single day in the headlines:

- The president declaring that there were “some very fine people on both sides” of the Charlottesville, Virginia white nationalist rally in 2017

- The spike in hate crimes in 2017 (up 17% from the previous year)

- The Pittsburgh synagogue shooting

- The litany of police shootings of unarmed black women and men

- The easy re-election of Iowa’s Representative Steve King, a known white nationalist sympathizer.

But one need not even go that far

In fact, just 20 miles from Wisconsin’s liberal bastion of Madison, a little bedroom community of 7000 has its own serious issues with hate and bullying. Mount Horeb, the “Troll Capital of the World,” made national news in 2015 when parents of a 6-year-old transgender child suggested that her school class read the book I am Jazz, a story book written by 18-year-old transgender activist Jazz Jennings.

The school district, amid threat of a law suit by the hate group Liberty Council, refused to have the book read in the school, and allies decided to hold a reading of the book at the public library instead. The reading ballooned into a 600-person show of solidarity, and which sparked a national movement, led by the Human Rights Campaign, to hold similar public readings of the book in solidarity.

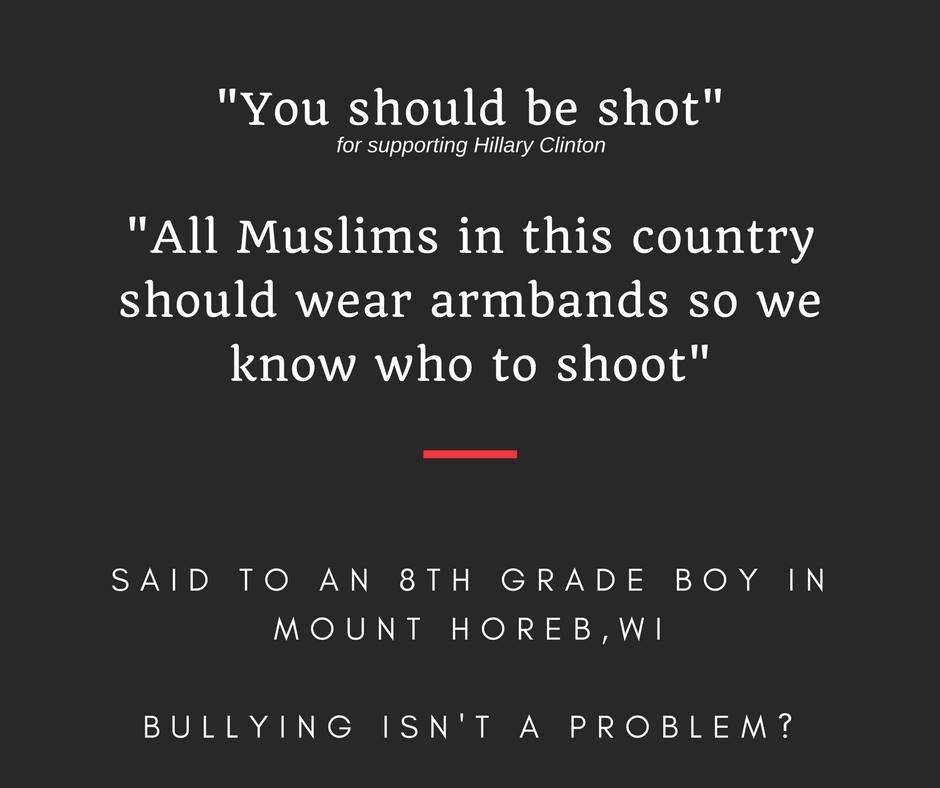

Yet despite the public outpouring of support, Mt. Horeb continued to struggle with issues of hate, bullying, and intolerance. A Jewish family who lived in the town from 2008-2017 found their eldest child subject to intense bullying and anti-semitism, including online threats. At the school’s annual fun run, the mother documented chalk messages written by 8th graders on the run path and brought them to the attention of other parents.

The mother said, “I was volunteering and my final job was to check the chalk to make sure it was all positive. It wasn’t and I lost my mind, and the parents with me were like ‘Oh those kids have no idea what that means. No idea what they are saying.’ I did the whole ignorance is not an excuse speech and left. That same year a kid came up to my son and said, ‘I looked up the name for a Jewish n*****,” and proceeded to call my son a k***.”

Those weren’t isolated incidents, either. Her son discovered a swastika scrawled under the table in his Language Arts class. The family felt the teacher was more concerned with the discovery of defacement of property rather than the antisemitic symbol, which they saw as an isolated incident.

By early 2017, the family hit a breaking point. The bullying of their son had intensified, and upon consultation with a therapist, the family decided to leave the community to move back to a more diverse area.

Additionally, from 2017-2018, three current or former students in Mt. Horeb died by suicide, rocking the community. In 2017, a high school student indicated via the app SnapChat that he was going to kill himself, and then carried it out. In July of 2018, two young people from Mt. Horeb died by suicide– a 20-year-old and a 19-year-old.

Though it’s not clear that the suicides are linked to bullying, anecdotally and in private conversations with parents, many indicate that bullying is a prevalent issue, and one that’s being addressed as a mental health issue, but not a larger communal issue.

The Way Forward

The question that remains is what to do about Baraboo. What to do about Mt. Horeb or Wisconsin or Iowa or the United States. What is the cure for hate?

Certainly, the Jewish family from Mt. Horeb found some relief by moving out of the community. Few people would find fault with the idea of, after trying again and again to get the school community and the town to engage with the problems (or, in some cases, to even acknowledge them as problems), deciding to pull up roots and move. But that’s simply not an option for many folks, for whom work or family or lack of resources makes it an impossibility.

In small town and rural America, is it enough to just survive, try and fly under the radar, and hope one day to escape?

In Baraboo, there will be tough decisions to be made, and those decisions will be highly scrutinized not only by the town, but also by the world, now that the story has gone viral internationally.

Jeff Spitzer-Resnick, the president of a Madison-area synagogue which has congregants in Baraboo, suggested in an open letter to the Baraboo School District that they take the viral photo seriously and engage in a holistic approach to addressing the antisemitic act. This approach would include fostering better critical thinking skills, learning more about the historical context of the gesture and the Holocaust, as well as a restorative justice component.

It’s important to note that, while many school districts require some Holocaust or Genocide component to their history requirements, relatively few US states require all of their schools to teach these things, leaving it up to local school boards to decide what version of history to teach, and what to include.

Yet most advocates would say that no one approach or effort will truly inoculate a community against hate. There is a tendency, after incidents garner headlines, for commentators and experts to rush in and judge.

There is a tendency for some faction of people to steel themselves against what is being reflected– this is not who we are. There are others who will say this is how we’ve always been. And there are those who won’t or can’t speak, because they’re afraid that when the spotlights leave and things go back to normal, that things will go back to normal, and that normal is not good.

For America to change, for these small towns to change, for these people to change, the status quo is going to need to become too uncomfortable to stand. While we are often told to forgive and forget, these towns, these people must not rush to do so. Forgive– yes, when repair has been undertaken. Where goodwill is not just a one-time event, but a process that is committed to.

But forget? No. To forget means to erase. America is demonstrating the results of forgetting every single day– history reenacted like a dark production of Our Town, all across America. Without the names of places or identifying landmarks, these towns are every town. These incidents are all of the same genesis, have the same DNA. It’s up to the players to acknowledge the pattern and the roles. It’s up to them– and us– to adopt processes and strategies and supports and cultures that reinforce them. America, you are patient and doctor.

The discomfort we feel now is part of the solution, not the disease.

Corrections: An earlier version of this story suggested that the parents of the transgender child in Mt. Horeb wanted the book to be read because of bullying. The impetus for the book to be read in school was clarified as the child’s social transitioning of their gender identity. Additionally, an earlier version of this story mistakenly created a causal relationship between the rash of suicides and bullying. This has been further clarified in the text.